We hear every day how we’re living in uncertain times; and it’s true: in a thousand ways we are circumscribed by a great murmuration of unknowns that flock as far as eye can see, jabbering and spreading panic from here to Timbuctoo.

But, then, the times are always uncertain! We like to think we’ve banished unpredictability, or reined it in … with, what?, Border security? Biometric Iris Scanning? CCTV? …

Each, no doubt, has its place, though none of them spares us the heartache, and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to. Which is why we have such an appetite for it; craving certainty like sugar.

It’ll be why we like our politicians to do what they’ve said they will; and why the Press never hails a change in course as an intelligent response to fresh evidence, always preferring to pillory hapless and the witless for weak-willed infirmity of purpose. ‘You turn if you want to,’ as Mrs Thatcher once said; ‘the Lady’s not for turning.’ Thank you, Lord Copper; and we’ll be coming back to you later in the programme.’

St Paul was another who was quite certain he was certain, and who must have been significantly discombobulated by all that befell him on the Road to Damascus as he went off in search of more pesky Jesus-types who were leading honest folk away from the faith of their fathers, into heaven only knew what quagmire of heresy and uncharted error.

But then Paul was always ripe for reform: he was a fanatic – shackled to certainty. And, as we have had cause to observe before, a fanatic can be beaten because – to quote George Smiley – ‘the fanatic is always concealing a secret doubt.’

You see it sometimes: in the eyes of those who are peddling some sort of totalitarian creed – whether it’s the inerrancy of scripture, or the irredeemable wrongness of people because of their beliefs or colour or sexual identity. In all the outpouring of well-rehearsed bile and bonkers bravado, you see just the hairline crack of a question. Or you hope you do.

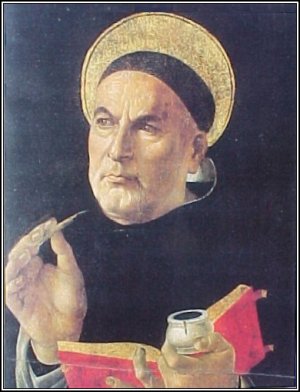

St Paul’s misleadingly-named ‘conversion’ was celebrated on Monday. He shares January 25th each year with the Scots poet Robbie Burns, a propinquity that must make for interesting conversation over the heavenly haggis. Today, the Church keeps another big hitter – to whom I know the theologians among you have a particular devotion – the Angelic Doctor himself, St Thomas Aquinas.

Undoubtedly Thomas was very clear in his theological and philosophical thinking – perhaps to the point of certainty; which makes all the more extraordinary his setting-aside of all his work just a few months before his death, declaring to his faithful companion, Reginald of Piperno, ‘I can do no more: all that I have written seems like straw. Omne foenum. All straw! What had happened to the big man? A stroke? A breakdown? An ecstatic experience?, in which he saw that all his theological effort to set down in words the glory of heaven was halting, transitory? Straw?

I hope that Thomas, like Paul, simply realised that, for all his disciplined piety and sublime theological dexterity, the Mystery of God would always be far more capacious than their respective architectural and legalistic constructions could quite express.

Perhaps they found what many do: that, as you grow older, you tend to believe far less about God, though you believe it far more.

All of which suggests to me that those who pore over the works of this blest pair of Giants determined to find support for a smorgasbord of unpleasant opinions, are missing the point by a country mile. Diminishing and dismissing others simply on the grounds of who they love and how they live, is a very far step from the Paul whose dense singularity was exploded by a new conviction that God could not be contained in the confines of a single tradition; and from the Thomas who stepped back into silence not pour mieux sauter, but to see things rather more clearly than before.

I wonder where you think that leaves you? I cannot know! I don’t know how much certainty you need, though I’m guessing that there’s a fair bit about life just now that is, to use the argot, doing your head in. Many of you will certainly identify with these two saints and find in their disruption recognisable traces of your own.

As the blessed Burns puts it, The best laid schemes o’ mice and men/Gang aft agley …

Our response, perhaps, is not simply to replace one broken certainty with hope of another, but to live with a sort of alert provisionality, responding to events as they do, in fact, unfold, all the while preparing and readying ourselves for whatever unpredictable number the cast die reveals. In all of this, we’ll need to stick together for support. Uncertainty and vulnerability go together. And are best countered by solidarity – among friends, in the family, and of course in school. No doubt, like Thomas and Paul, we will discover that our world and its questions are bigger and more demanding than we had imagined. And perhaps, like them, we will have to consider new ways of tackling them. As we do so, we need not fear revisions or a change in plan. With the grace to imagine that we may be wrong, and the willingness to respond as new evidence emerges, we will avoid the brittle certainties of the fearful fanatic, and learn to dance a giddy U-turn of our own. Through all the unknowns, together we will come, even to the ‘promised joys’ of tomorrow.

A homily for Magdalen College School, Oxford, 28 January 2021